Forgiveness, pardon and reconciliation

This week has brought many deep reflections for me. Like many I was stunned four years ago when I watched what might have been the peaceful transfer of power erupt into violence that threatened the United States’ governance. I have lived much of my life in parts of the world where brawls and physical fights in the national assembly were common. Political rivals would simply “disappear”, the local euphemism for a discreet murder. Then in 1997 when I was working on my PhD dissertation in South Africa I witnessed one of the most amazing sights of my life.

I sat in a hall with several hundred South Africans—white, black and colored—and watched the Truth and Reconciliation Commission carefully question and listen to Winnie Mandela’s testimony as well as counter testimonies of the “accidental” death of a Stompie Seipei. According to the South African press, Winnie was convicted in 1991 of kidnapping Stompie but was acquitted of the murder and her sentence was commuted so that she was never jailed.

At noon that day the proceedings (not a trial) broke for lunch and I returned to the hall early for a better seat. I sat nearly alone in the hall and recognized a familiar profile standing only about 15 feet away from me. As the television cameras trained into the hall, the figure turned and I realized that indeed it was Nelson Mandela himself who had come to the hearing that dealt with the actions of his first, and at that time former wife. His commitment to non-violence and had given him 20 years in prison isolation as result of his political stands, even as violence increased in the country. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission was created under his administration as president with the belief that when a person told the truth about what they had done, no matter how horrible, then they could be given amnesty for that act if it had been done for a political end.

Many Christians found the TRC principles to be unacceptable. It did not require a person to have any remorse for what they had done. Acts could have been done without any seeking of repentance. So how could there be reconciliation? Many white South Africans felt coerced into the findings of the TRC. Many black South Africans felt grave injustices had been overlooked.

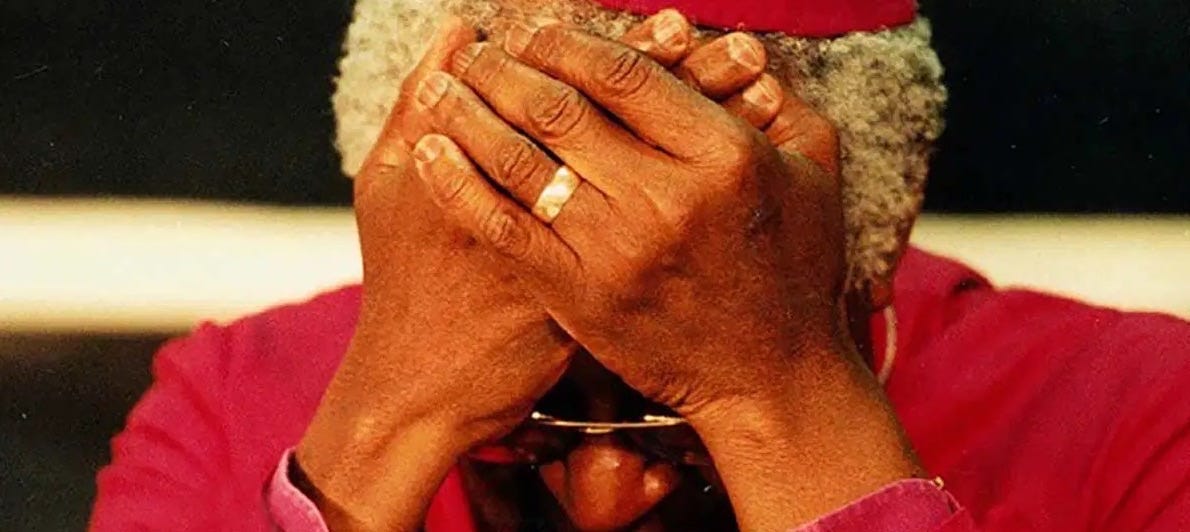

But that day I watched Nelson Mandela look at a process of national and political forgiveness of which he was a part. He honored the process of a TRC that was composed of those who had been his bitter enemies as well as friends. The country began a route to healing. Nelson was not protected by a squadron of military, or sycophants. He led a deeply divided country in grace, in gentleness, and in grace. Meanwhile his former wife responded to the pleading of Archbishop Tutu that she identify her role the day Stompei had died. “Things just went wrong,” was her simple denial that she was a part of the wrong other than to be a bystander.

We have in this past week been in a virtual hall watching the forces of government grant pardons, commute sentences, and mandate a justice department to bring to investigate and charge any official failing to pursue an agenda of a new president. So we do well to ask what place pardons and commutations have in politics of a divided country. Do they bring reconciliation?

If, on the one hand a president makes a “preemptive pardon” has he in fact passed a personal judgement that the actions taken were indeed wrong and therefore needed pardon? If he pardons because he believed that a political process drove an investigation is it different than what happened with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission? If a president pardons and/or commutes the sentences of those who have had the privilege of a court trial (which was lacking in South Africa) has he undermined justice or has he shown mercy?

I will not attempt to answer the questions, rather I want to draw some principles from political pardon and forgiveness as I witnessed it in South Africa:

1. A political pardon is valid based on the office or position of the one declaring it.

2. A political pardon has value based the declaration being made by a neutral party who has no benefit from the pardon.

3. A political pardon cannot bring reconciliation unless there is recognition by the wrong doer that a wrong was done.

4. A political pardon may invoke revenge and retribution when it mainly validates the pardoner.

5. A political pardon may help in reconciliation of diverse parties to the extent it is seen as position-neutral.

6. A political pardon must be based upon established truth-telling.

7. Truth-telling is established in the hearing of multiple perspectives.

8. Reconciliation is helped by truth-telling, but cannot be guaranteed.

9. Reconciliation requires some compensation for the party wronged.

10. There are different kinds of forgiveness, but the forgiveness that brings reconciliation is one that removes penalty and restores community.

Africa has much to teach America. I encourage you to reflect on the TRC and the USA. Anything less than the spirit of the TRC cannot lead to greatness, but even the spirit of the TRC could not remove flaws that brought later failures in South Africa. Christian forgiveness and reconciliation must be more than the political forgiveness of the TRC, but it cannot be less.